I feel in love with a painting at The Met when I went with Hansel a few weekends ago. It’s called The Ameya and was painted by Robert Frederick Blum in 1893. Blum went to Japan to illustrate a series of articles for Schribner’s Magazine, and this painting shows a candy blower surrounded by passersby who stopped to take a look.

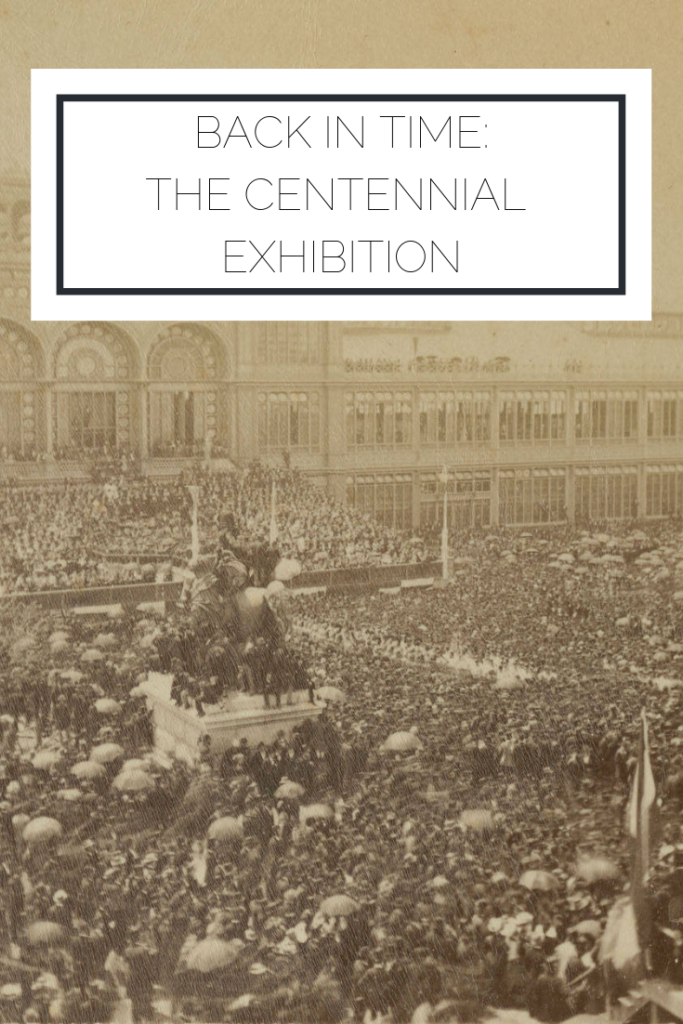

Blum went to Japan in 1890 to attend the Third National Industrial Exhibition, which ended up being a domestic event that only drew 246 visitors from abroad. As you can imagine, this event isn’t too interesting to talk about, but the event that inspired Blum to go to Japan and attend the Third National Industrial Exhibition is far more fun to dive into. Get ready to learn about the Centennial Exhibition – the first official World’s Fair!

If you’ve read The Devil in the White City, you’re familiar with both a serial killer and with the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago in 1893. Both tales have a lot of drama and make me long for the days of large-scale celebrations of countries, a la Epcot. As you can imagine, if the World’s Columbian Exhibition had drama, then the Centennial Exhibition has to have its own host of interesting stories.

Let’s first go over the basic facts. It’s 1870. The centennial anniversary of the Declaration of Independence is coming up in six years. John L. Campbell, a professor of mathematics, natural philosophy, and astronomy tells his friend, the mayor of Philadelphia, Morton McMichael that he has a great idea for how we can celebrate. John suggests an exhibition and Morton is in.

In order to hold what would be a massive event, the city of Philadelphia needed the support of the U.S. Congress. Congressman William Kelley (a friend of Abraham Lincoln and founder of the Republican party) spoke for the city and state, and Daniel Morrell (general manager of the Cambria Iron Company, the greatest manufacturer of iron and steel in the U.S. … until the Johnstown Flood literally wiped the plant out and killed more than two thousand people. It’s crazy, look it up) was the one who actually introduced the bill. The big selling point was that Congress would not be on the hook for any expenses, so unsurprisingly, they gave the go ahead to Philadelphia to have their exhibition.

Unfortunately, while the people of Philadelphia were able to raise a good amount of money, they were still a bit short and ended up getting $1.5 million from the federal government. There was a “misunderstanding” and the exhibition committee (made up of members from every state) thought it was a gift, while the federal government meant it as a loan. The federal government ended up having to sue the committee after the fact and the Supreme Court told the committee they had to repay the loan.

I could go on and on about other interesting facts concerning money (like the fact that they actually chartered a bank, The Centennial National Bank, which is now regarded as one of the best pieces of architecture in West Philadelphia. Big praise. And how they built a hospital and tons of housing in preparation for the influx of people) and promoting the event (John Forney went to Europe for two years and not a single nation that received an invitation turned it down. I bet there are some good stories there), but I think it’s high time we get into what was actually at the exhibition and what Robert Frederick Blum saw there that got him so jazzed up about Japan and attending the Third National Industrial Exhibition.

The official name of the Centennial Exhibition was International Exhibition of Arts, Manufacturers and Products of Soil and Mine. There was a main exhibition building, an agricultural hall, a horticultural hall, a machinery hall, an art hall (the largest in the country when it opened), a women’s pavilion, and a number of other buildings. Just to make sure I tie things back to Ben Franklin (as you know we have to have a founding father in every post), there was a Women’s Centennial Executive Committee, headed by Elizabeth Duane Gillespie who was a descendant of Ben Franklin, and they pushed to have representation of women and women’s contributions; hence the women’s pavilion.

The most exciting sights at the exhibition ranged from vendors selling bananas (considered a delicacy at the time) to the Corliss Steam Engine. Heinz ketchup made its debut, Alexander Graham Bell showed off his telephone for the first time, and the Statue of Liberty’s arm and torch were on display while Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi was working on the rest of it.

But what about the Japanese contribution to the Centennial Exhibition that so impressed our friend Blum? Well, just as the U.S. was trying to show that world that it was a force to be reckoned with post-Civil War, Japan wanted to be just as well respected and show how far they had come in their efforts to modernize and attract trading partners. The Japanese kept their exhibit simple and demonstrated their eye for design and quality craftsmanship that impressed many of the exhibition-goers.

With over 10 million visitors, thirty-seven country participants, and seven months of operation, the first ever World’s Fair set the bar for international celebrations and showed how proud and ready the Americans were to celebrate 100 years of freedom and come back from the devastation of the Civil War.

Leave a Reply